Japan's wage talks key for future of Abenomics

HISASHI Aoto was not holding out much hope that his employer would give him a bumper pay rise this year as Japan's spring labour talks wrap up.

The 44-year-old is among the millions of rank-and-file workers eyeing the annual union negotiations, as top companies including automakers Toyota and Nissan, conglomerate Hitachi and electronics giant Panasonic announce their pay plans from Wednesday.

"My employer's financial results were bad this year," said Aoto, who works in the sales department of a major computer and software maker.

"I don't think there is any chance of my salary rising," he added, ahead of the announcements.

That gloomy outlook is not good news for Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who has been pushing stingy companies to boost workers' wage packets.

His increasingly desperate calls are borne from a hope that more pay will mean more spending, which is crucial if Abe's plan to lift growth has any chance of success after three years of lacklustre results.

Many more firms will make wage announcements in the coming weeks, but union bosses are unlikely to be cracking open the champagne.

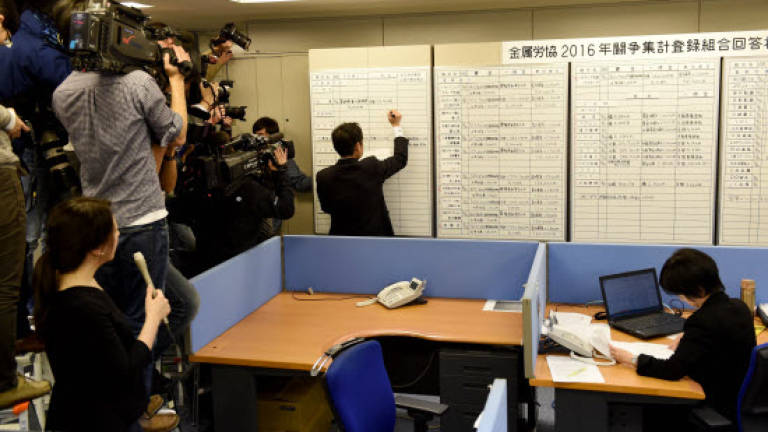

Despite record profits, Toyota said on Wednesday it would lift workers' monthly pay by just ¥1,500 (US$13, RM53.79) – although it is also raising twice-yearly bonuses – while Hitachi, Fujitsu and Panasonic will hike wages by the same amount.

Honda said its basic wages would increase ¥1,100, while Altima sedan maker Nissan was a bit more generous, announcing a ¥3,000 jump.

Workers at Japan's biggest banks did not even ask for wage rises, as a widely criticised negative interest rate policy by the Bank of Japan threatens lenders' bottom lines.

'Income disparity'

Japan's firms are growing more cautious as the world's number three economy, which contracted in the last quarter of 2015, runs up against slowing growth overseas, weak spending at home and a stronger yen, which is bad news for exporters.

Until recently, the yen has been falling as massive monetary easing by the BoJ – a cornerstone of Abe's big-spending, easing money policy drive dubbed Abenomics – helped push down the currency.

The weak yen fattened exporting firms' profits, but the unit has strengthened recently and few cash-rich companies now seem willing to open up their war chests.

Many smaller firms that never reaped the rewards of a weaker currency are not in a position to raise pay, said Rikio Kozu, the boss of the 6.8-million member Japanese Trade Union Confederation.

"There are many companies where regular wage increases just couldn't happen," Kozu told AFP in an interview at his union's national headquarters in Tokyo.

"Income disparity has been going up over the past two years. If that keeps happening, there is no way to beat deflation."

While Japan's consumer prices were on the upswing for a while, they have fallen back, forcing the central bank to push back its timeline for a 2.0% inflation target.

The once-soaring economy has struggled against deflation for years, as consumers hoped to buy stuff cheaper down the road.

But that lack of spending hurt expansion and hiring plans, while stagnant prices gave companies little incentive to boost pay.

'Squeezing a dry cloth'

More recently, the slowdown in key export markets such as China is offering companies another excuse to avoid inflating their fixed costs like salaries, said Martin Schulz, senior economist at the Fujitsu Research Institute.

"Remarkably, trade unions share this view," he added.

"They are well aware of the dilemma – they are scared about new waves of cost-cutting and restructuring when costs start to increase too fast."

About 1,300 representatives from the country's unions this month met at a boxing venue near the giant Tokyo Dome.

But the talks, known as Shunto or "the spring offensive", tend to be anything but a slug fest these days, unlike in past decades when strikes and work slowdowns were common.

The number of strikes peaked at more than 5,000 a year in the mid-seventies, involving around 3.6 million people. Nowadays, a few dozen strikes by several thousand workers are the norm.

It is a far cry from Europe's factory-shutting labour disputes or vocal strikes in South Korea and rising worker unrest in China.

But for many Japanese unions, generous pay and bonus hikes are a pipe dream – avoiding mass layoffs and protecting worker's welfare are the priorities.

For businessman Kiyoshi Wakai, little will change on the pay front – or for the success of Abenomics – until Japanese firms focus more overseas, rather than cutting costs to compete with domestic rivals in a shrinking market.

"It's like Japanese companies are squeezing out a dry cloth," said Wakai, president of Cadex, which supplies cleaning equipment to the aviation industry.

"Even if they squeeze and squeeze, there's no water coming out." — AFP